World War I - Narratives of war

These are accounts of the fighting and its effects as seen by those directly involved. They are only some of the stories which can be told of the men and women of Royston and are set out in their own words or in the words of others who reported on their courage.

Click the names below to access their stories.

- Harold Ackroyd

- Alex Everett

- Grace Bullard

- Herbert Sermons

- Eric Phillips

- Walter Anderson

- Frederick Feast

- Leonard Godfrey

- Herbert Norman

- William Reed

Harold Ackroyd

VC, MC

Captain

Royal Army Medical Corps

attached to 6th Battalion, Berkshire Regiment

Harold Ackroyd

Wellcome Library, London

Captain

Royal Army Medical Corps

attached to 6th Battalion, Berkshire Regiment

Harold Ackroyd was educated at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, and Guys Hospital, London gaining an MD in 1910.

Granted a British Medical Association scholarship at Downing Research Laboratory, Cambridge, he moved to Royston, living at “Brooklands”, Kneesworth Street with his wife Mabel and their three children.

He was awarded the Military Cross for his actions during the Battle of the Somme. He was allowed home to rest and recover from the effects of working under such pressure before returning to the the front line.

Harold Ackroyd was shot in the head by a snipper whilst attending wounded soldiers. He died 11 August 1917 aged 40 and is buried in the Birr Cross Roads Cemetery, Belgium.

He was postumously awarded the Victoria Cross, his wife collecting it on his behalf from the King.

Military Cross

For the award of the Military Cross, Temporary Captain Harold Ackroyd, MD, Royal Army Medical Corps.

"For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty during operations. He attended the wounded under heavy fire, and finally, when he had seen that all our wounded from behind the line had got in, he went out beyond the front line and brought in both our own and enemy wounded, although continually snipped at."

London Gazette, 20 October 1916

"He seemed to be everywhere; he tended and bandaged scores of men, for to him fell the rush of cases round Clapham Junction and towards Hooge. But no wounded man was treated hurriedly or unskilfully. Ackroyd worked as stoically as if he were in the quiet of an operating theatre. When it was all over and the reports came in, it was found there were twenty-three separate recommendations of his name for the Victoria Cross."

From a report by the 18th Division historian

Victoria Cross

For the award of the Victoria Cross, Ypres, Belgium, 31 July to 1 August 1917, Captain Harold Ackroyd, MD, Royal Army Medical Corps.

"Captain Ackroyd worked continuously, utterly regardless of danger, saving lives and tending to the wounded men in the front line under heavy fire. Having carried one wounded officer to safety on his back he returned to bring another under snipper fire. His heroism was the means of saving many lives, and provided a magnificent example of courage, cheerfulness and determination to the fighting men in whose midst he was carrying out his splendid work."

London Gazette, 6 September 1917

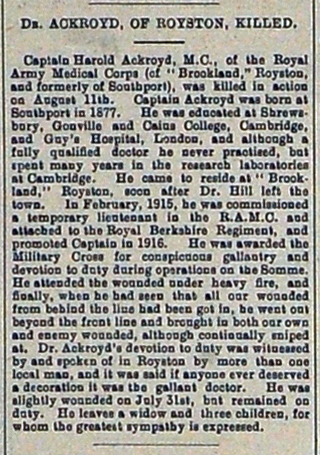

Reports in the Royston Crow

Captain Ackroyd’s death

The edition of 24th August announced the death of Captain Harold Ackroyd of the Army Medical Corps. The article covered his education and army career.

At the time the extent of his bravery was not widely known.

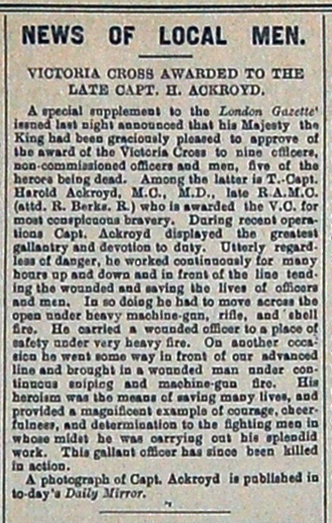

Award of the Victoria Cross

It was not until 7th September that readers of the Crow discovered that Captain Ackroyd was to be awarded the Victoria Cross for most conspicuous bravery.

Alex Everett

Lance Corporal

8th Battalion, Leicester Regiment

Lance Corporal

8th Battalion, Leicester Regiment

"On Thursday May 2nd 1917, the 8th and 9th Battalions were ordered to attack the lines about 4 o’clock in the morning. The Germans retreated from their first line to their supports. We lost the biggest part of our men and were then held up and surrounded. We held on for about 6 hours and at the finish there were only 92 prisoners taken and about 5 or 6 got back. That was all that remained of the two battalions. Fritz bombed us clean out.

"All the prisoners were searched and the first things they took were our first aid field dressings and left us nothing. The Germans had only paper bandages so they were glad to get ours. They refused to give our wounded any assistance or even a drink. We had to carry our wounded and were marched up to a village which we reached in about 3 hours. I do not remember the name of the village. We were put in a church for about 3 hours and then they marched us on to Donai. The wounded were given no attention and we had nothing to eat until Saturday, only what the French civilians gave us.

"We were afterwards taken to Fort Lille where we remained for about 8 days. There we got a 3lb loaf of black bread between 11 of us and a little so called soup which we had to eat from our steel helmets. From there we were taken to Epinoy and put in huts. We lay on the floor with no blankets. We were put to work on a railway dump from 5.30 am to 3 pm.

"On 11th June we were marched to Bouchain about 15 kilometres from Cambrai. There we were pretty badly off for food. We have eaten cats and dogs, stinging nettles, potato peelings and so on but that is nothing. I don’t want to talk about it. We were very badly off for clothes and had no boots.

"We were put to work on an ammunition dump and were bombed by English aeroplanes and Lance Corporal Brown, a Newfoundlander, was killed. We got no letters or parcels from home as during all this time our address was given as Friedricksfield but we were never there.

"On 2nd November we were sent to Schniedemuhl in German Poland. We were there only about 5 days with one loaf between 7 of us and a little soup. We had only wooden shoes and were set to cut down trees in 2 to 3 feet of snow. We slept in a small wooden hut in our clothes and we had no blankets; we did have a bit of a fire or we should have been dead. We were each served out with one 3lb loaf a week and a few boiled potatoes.

"Early in March we returned to Schiedemuhl and were then sent to Tremeesen about 18 kilometres from the Russian border were we were employed by a German Polish farmer and there we got on well for food. We had the best they were able to give us. Our first parcels from home did not arrive until February.

"As soon as we heard the Armistice was signed we left our horses and came away on our own. About 60 of our men died from influenza at Schiedemuhl. It need to cost us about 250 marks to properly bury our comrades. They would have been just thrown into a hole had we not done this for them. Where did we get the money? Once we got our rations of German bread and sold it to the Russians. We were then receiving our parcels regularly. Germany was fairly starved at any rate wherever I have been and the people were always wanting to buy the content of our parcels.

"We sailed from Danzig and reached Leith on Wednesday 18th December then we were sent to Ripon and came home on December 20th.

Grace Bullard

Governess

Charleroi, Belgium

Grace Bullard was among the many English men and women stranded in Europe when war was declared in August 1914.

Grace was born in October 1897, the youngest daughter of Louisa Mary and Charles Bullard of the High Street, Royston. She went to Belgium in early 1914, employed as a governess to teach English to the children of a Belgian family in Charleroi.

Governess

Charleroi, Belgium

The following is the account of her experiences, in her words, given in an interview to the Royston Crow.

Grace never married and died in 1984. Her death is recorded at Chichester, Sussex.

"I went to Belgium in March 1914. The first few months were quite uneventful until the war began on July 31st. We soon heard of the fall of Liege and Namur but as no newspapers were published, we did not know that the Germans were approaching Charleroi so rapidly until we heard the roar of the cannons. This was on August 2nd and the Germans came into the town about mid-day, setting fire to the houses by throwing lighted torches into the windows as they came along. Their excuse was that Belgian civilians had fired on them but this was not true. In this way about 300 houses were burnt down. We stayed down in the cellar that night. Next day the town was very quiet, but we could hear the cannon still roaring a little further off and the people were very frightened, as the Germans said that if a certain sum of money was not given up that day the whole town would be burnt down. The following day 5,000 Belgian and French prisoners were brought into the town and accommodated in the schools. A few days later four English prisoners were brought to the hospital, and I went to them very often, but unhappily two of them died. From this time onwards we lived under German Rule, the German Officers being billeted in the houses. Food became very scarce, as the Germans took so much to feed their troops. It was the food from ‘The American Relief in Belgium’ that kept us all from starving.

"On March 14th, 1915, all English, French, Italian and Russian (men and women) had to go to a German Bureau to be registered. After that we had to go once a week to have our cards stamped. Once I went to Brussels for a few days and on my return a German soldier came to fetch me with a fixed bayonet because I had not been to have my card stamped. Madam saved me from having to go with him by explaining in German that I had been away. Later on we had to have passports when we wanted to go out of the town. Once I was sent for to go to the barracks, and I was made to wait a long time in a room with a lot of Germans. After a while they took me into another room and asked me a lot of questions about my family. I think it was to try and find out if I received any letters from England.

"On several occasions placards were put up on the walls commanding the Belgian men of all classes between 18 and 40 to present themselves at a certain place. Many of these were marched off to work in Germany, and some of them returned half starved a few months later. Some of them were sent to the far north of Germany and died there of cold and starvation. The indignation of the Belgian women was indescribable. When the Germans required offices they would take an empty house and demand the town to furnish it. When they moved on they took the furniture with them, and the next lot would want the house furnished again. Also when they bought their wounded in they would demand the town to supply beds, blankets, sheets. If these things were not forthcoming the town was fined.

"During 1917 the Germans seemed to be getting to the end of their supply of brass, and ordered the Belgians to give up all they had in their houses. Many of the people gave up a very small quantity and buried the rest in their gardens.

"On April 12th 1918 we were bombed by English aeroplanes and we again had to take refuge in the cellar. On September 27th 1918, the Germans asked me if I would like to go home or not. As they had asked me this question four times before and the train had not gone, I said I would stay, especially as we thought the end of the war was in sight.

"On October 6th 1918, we first heard that the Germans had asked for peace. Between this time and the Armistice I saw several batches of England and French prisoners who had been in camps at the back of the German lines and were on their way to Germany. Many of them were harnessed to great carts, and forced to drag heavy loads. Among them I found a man from Cambridge. He told me that the Germans had given them no food since the night before, and this was 5 o’clock in the afternoon. We also found that there were several English prisoners at the hospital. Those that were well enough used to come to the window and we threw them bread and apples. After a day or two the Germans found this out and barred the window so that it could not be opened.

"During the last fortnight before the armistice we were kept excited by English aeroplanes trying to bomb Charleroi station and munition dumps and we had to spend a great deal of time in the cellar. A good number of people were killed. But these casualties were usually caused by shrapnel the Germans fired at the aeroplanes.

"On November 11th, at 9.00 o’clock in the morning we heard that the armistice had been signed. For the next few days we saw nothing but German motors, carts (piled up with furniture and stolen objects and pulled by oxen or men) lorries and soldiers all on their homeward way. Before the Germans had all gone the people began digging up their brass, one man put all his in his shop windows and wrote up in large letters ‘You see we have delivered the brass to the Germans’.

"On November 13th, the prisoners began to arrive in Charleroi – English, French, Italians and a few Russians. They had been set free the day before and had come on foot many miles without food. They were made a great fuss of by the civilians and great many of them were lodged in their houses, but next day so many arrived that they had to be billeted in the schools. Fresh batches kept arriving every day each looking more miserable than the last. They were all given a good dinner in a big hall and served by the ladies of the town. Some of them were so ill that they had to be taken to the hospital. 8,000 prisoners passed through the town in three days. As they became rested they marched on to meet the English troops.

"During the night of November 14-15th, we were awakened by most terrific explosions, but we could not make out what it was. In the morning we heard that several Germans had set light to trains and munitions dumps. Two of them were caught at the job and shot, but several of them changed into civilian clothes and continued the destruction in the villages around. The explosions kept on all day and we dared not go out much as great pieces of shrapnel were falling in the streets like rain. Windows were smashed in all parts of the town and in places a number of houses were burnt down and several people killed. The village of Jamionx near Charleroi was destroyed. The following day the Burgomaster of Charleroi went to Mons to request that English troops should be sent into the town to keep order. A few days later English troops marched into Charleroi and were welcomed with great enthusiasm. No one objected to their being billeted on them.

"After a few days I applied for a passport to return to England, but it was a month before I could obtain it. Even then the journey seemed impossible as there were no civilian trains running. On December 3rd, and English Officer sent me and three other English girls to Boulogne in a motor lorry. The journey took us 10 hours and we came through Mons, Valencienne, Donai and Arras seeing a part of the devastation of the country.

"We crossed to Folkestone on a ‘leave boat’ on Sunday, December 22nd and arrived home the next day."

Herbert Sermons

Sargeant

Gallipli

Sargeant

Gallipli

An eye-witness account from Sergeant Herbert Arthur Sermons of Royston who landed at Suvla Bay, Gallipoli in August 1915. Upon arrival at the Dardanelles he wrote to his old schoolmaster in Royston, Mr. C Attridge. He says:

“No doubt you have heard of the work which has been carried out here in the Dardanelles. I can assure you that although our division has only been out here a short time we have seen some very rough work, and I am thankful to be alive. We are now having a few days rest and I think the lads deserve it. Whilst we have been in our rest camp we have been under the fire of the Turkish guns, which makes us to “get down and get under” as the song says.

“We live the life of hermits in dug-outs amongst the hills, trying to bury ourselves out of the way of the enemy who are very clever in soon finding out our positions. There are a large number of Germans amongst the Turks and I think it is they who are such good marksman. We get plenty of hill-climbing out here, which comes rather hard for us boys who are not used to it. It is very hot in the day and very cold at night. Water is very scarce, and we have to be sparing with it.

“One good point is that we are quite near the sea so that after a week’s hard work we get a bathe and it greatly refreshes us. Our food is good considering the circumstances. Biscuits, corned beef, jam, tea, sugar and occasionally we get rice and raisins. We hope before long to get an issue of bread by way of a change.

“My brother arrived here with the horses and mules about a week after we landed. He is in the pink of condition but not at the same place as we are. I never thought when I was learning of these parts at school that I should ever have the privilege of going to see them."

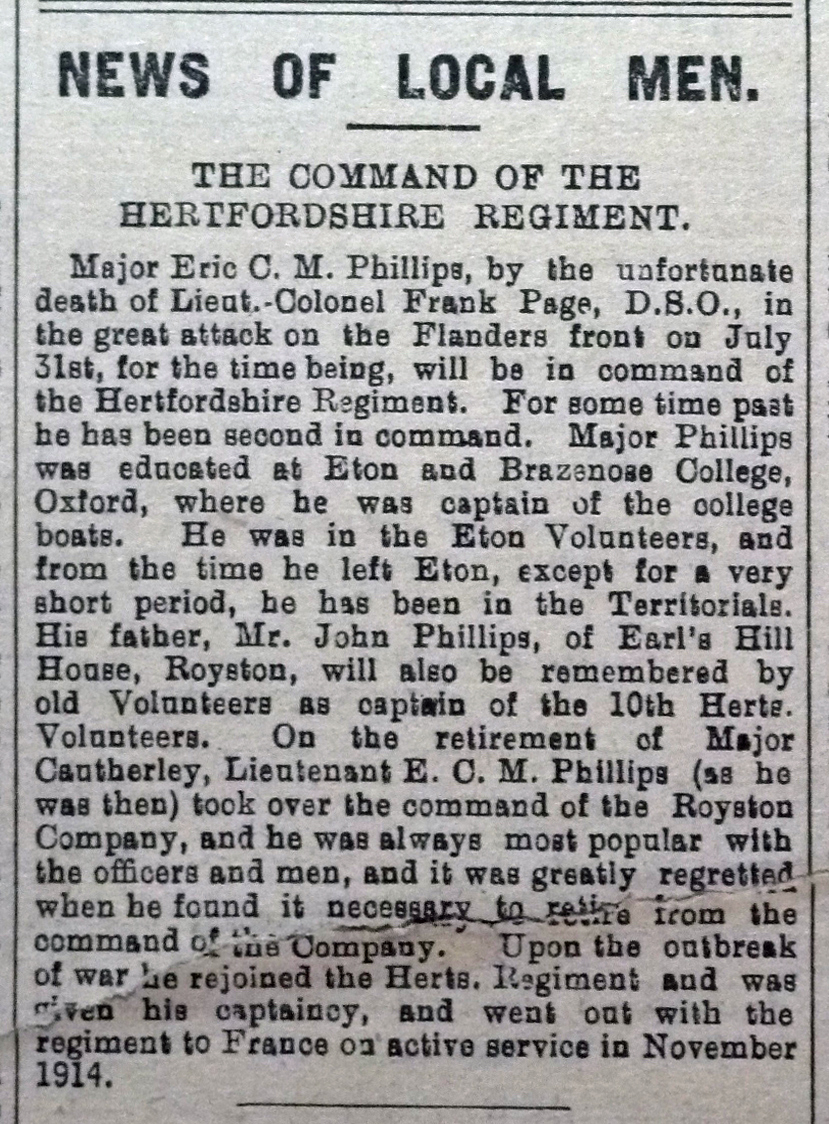

Eric Charles Malcom Phillips

CB, DSO, TD, DL, JP

Lieutenant Colonel

1st Battalion, Hertfordshire Regiment

Lieutenant Colonel

1st Battalion, Hertfordshire Regiment

Born in 1883 in Royston, son of John and Katherine Phillips of the family associated with Royston’s Brewery.

He joined the Hertfordshire Battalion of the Bedfordshire Regiment on 5th March 1902 with which he served until the formation of the Territorial Force in 1908. He resigned his commission in 1913 only to re-join as Captain in September 1914, shortly after the outbreak of the war. He served in France on active duty with the “Hertfordshires” as both Captain and Major from November 1914.

Following the disastrous attack on St. Julien on 31st July 1917 in which all officers of the 1st Battalion of the Hertfordshire Regiment were killed, including its then commander Lieutenant Colonel Frank Page, DSO, Major Phillips was given temporary command.

In August 1917 he was “gazetted” Lieutenant Colonel and given permanent command of the 1st Battalion until wounded by a shell at St. Julien in January 1918. The following March he was taken prisoner at Clerysor-Somme and remained a captive until December 1918, a month after the Armistice was signed.

For his services he was mentioned in dispatches and received the Distinguished Service Order. His name was brought to the attention of the Secretary of State for War for gallant and distinguished conduct in the field. He returned to the Hertfordshires as Major in 1920, acting as second in command. He received the Territorial Decorations in 1922 and was promoted to command in 1924. In 1928 he was further promoted to Brevet-Colonel and continued to command the Hertfordshires until 1931. He had been connected with the Regiment for 53 years when, in July 1952, as Joint Honorary Colonel with the Queen Mother, he took the salute for the last time at the Folkstone Camp.

In 1932 he was appointed A.D.C. to King George V. He also served in this capacity to King Edward VIII and King George VI. Appreciation for his services to the Territorial Army were shown when he received the honour of Companion of the Bath for his work in its support.

In April 1956 Colonel Phillips was knocked down in an accident while returning from a fishing holiday in Burford and, although he recovered from his fractured ankle, complications arose from time to time. He died in January 1957, aged 73, at the Royston and District Hospital from brochitis and heart trouble. All who knew him agreed that Royston had lost someone who took his military responsibities seriously and who was widely involved with the business and political aspects of life in the town.

Walter Frederick Anderson

Corporal

2nd Battalion, Lincolnshire Regiment

Regimental Number 10377

Corporal

2nd Battalion, Lincolnshire Regiment

Regimental Number 10377

Son of Lydia Ann Blows and Ebinezer Anderson, born Royston 1889.

Enlisting in the army in 1904, he served with the Bedfordshire Regiment in Gibraltar and Bermuda. When the war broke out in 1914, the regiment was recalled to the UK and Walter Frederick Anderson was transferred to the 2nd Battalion, Lincolnshire Regiment.

The History of the Lincolnshire Regiment 1914-18 compiled from war diaries, dispatches, Officer’s notes and other sources and edited by Major General C. R Simpson, Colonel of the Regiment describes an eyewitness account of the action taken by the 2nd Battalion of the Lincolnshires on the first day of the Battle of the Somme. It says:

"As soon as the barrage lifted the whole assaulted. We were met with very severe rifle-fire and in most cases had to advance in rushes and return the fire. This fire seemed to come from the German second lines and the machine-gun fire from our left. On reaching the German front line we found it strongly held and were met with showers of bombs, but after a very hard fight about two hundred yards of German lines were taken about 7.50 am. Our support company by this time joined in. The few officers that were left gallantly led their men over the German trench to attack the second line, but owing to the rifle and machine-gun fire could not push on. Attempts were made to consolidate and make blocks, but the trench was so badly knocked about that very little cover was obtainable. We were actually in the German trenches for two or three hours, and captured a lot more trench on our right by bombing as well as repulsing a German counter-attack from their second line. It was impossible to hang on longer owing to shortage of ammunition, and no more bombs, as we had used up all our own as well as all the German bombs we could find in the trenches and dug-outs, and were being gradually squeezed out by their bombing attacks. A company of the Royal Irish Rifles made a most gallant attempt to come to our support, but only ten or twelve men succeeded in getting through the zone of terrific machine-gun fire. We went into the attack with twenty-two officers, all of whom were killed or wounded. We first retired to shell-holes in ‘No Man’s Land’ and kept up fire on the trench we had left with ammunition we collected from the wounded. As it was obvious we could do no good there, we retired to our own trench and reorganised to be ready for another attack if required.

"Orders were received from the 25th Brigade to withdraw to Ribble and Melling Streets and occupy the assembly dug-outs, which was done."

Corporal Anderson was killed in action during the assault and is buried at the Ovillers Military Cemetery and remembered on the Royston War Memorial.

Frederick Charles Feast

Private

2nd Battalion, Bedfordshire Regiment

Private

2nd Battalion, Bedfordshire Regiment

Regimental Number 4/6129

Second son of John and Jane Feast of Hastings Villas, Gower Road, Royston, born 1896.

A grocer’s errand boy, he enlisted at the outbreak of the war in November 1914.

The village of Montauban lay behind the first German defensive system consisting of two trench lines along communication trenches. The second had three strongpoints: Dublin Redoubt, Glatz Redoubt and Pommiers Redoubt. This line was known (right to left) as Dublin Trench – Train Alley – Pommiers Trench. The village of Montauban, fortified with another trench line ran in front of it.

From a report taken from the war diary of the 2nd Battalion, Bedfordshire Regiment which says:

"The early morning of July 1st was hazy and from our positions we could not see the German positions. At 7.30 a.m. (ZERO Hour) the general advance commenced, led by the 17th and 20th Battalions Kings Liverpool Regt, the 2nd Battalion, Bedfordshire Regiment being in support and the 19th Battalion Kings Liverpool Regiment in Reserve. The Bombardment has been so successful that very little resistance from Rifle Fire took place, but most of the casualties were sustained from Shell Fire. The Headquarters of the Battalion were in the Chateau dug-outs during the preliminary advance.

"By 8 a.m. the German 1st Line Trenches were taken (including FAVIERE and SILESIA fire trenches) the leading Battalions pushing on to CASEMENT TRENCH – ALT ALLEY – GLATZ ALLEY, advanced and occupied FAVIERE SUPPORT – SILESIA SUPPORT and B & C Companies supporting the advance to DUBLIN TRENCH occupying CASEMENT TRENCH. At 12.30 p.m., the 20th Bn. Kings Liverpool Regiment assaulted and took the BRIQUETERIE. This was successfully accomplished and about 300 prisoners and 4 Machine Guns were taken, this work completed, the men re-joined their company who were under heavy shell fire during the day and night. At 8.15 a.m. the following day, Battalion H.Q., moved up into LEXDON STREET in our old front line trenches and remained there during the operation."

Private Feast is buried at the Cerisy-Gailly Military Cemetery and remembered on the Royston War Memorial.

Leonard George Godfrey

2nd Lieutenant

10th Battalion, Royal Welsh Fusiliers

Formerly Sergeant, 1st Battalion, Bedfordshire Regiment

Regimental Number 8087

2nd Lieutenant

10th Battalion, Royal Welsh Fusiliers

Formerly Sergeant, 1st Battalion, Bedfordshire Regiment

Regimental Number 8087

Son of Owen and Ellan Godfrey of Green Street, Royston. Born 1889, Chertsey.

Battle of Delville Wood : 20th to 21st July

"The 10th Battalion of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers, part of the 76th Brigade of the Army 3rd Division had been ordered to take up position at Delville Wood and to attack it from ‘Princess Street.’ Arriving during the early hours of 20th July, a failure in communicating the orders placed the 10th at ‘Buchanan Street’ right in the middle of the German lines. Surrounded by heavy machine gun fire, a close quarter fighting followed, resulting in 91 members of the battalion killed, dying of their wounds or missing. Among the casualties was 2nd Lieutenant Leonard Godfrey. He was in charge of the Battalion Scouts and was with the leading troops when he was killed instantaneously by a rifle bullet. He did not suffer in any way. Before he went into the fight he had rendered invaluable service in reconnaissance."

Leonard Godfrey is remembered at the Thiepval and Royston War Memorials.

Herbert Edwin Norman

Private

Machine Gun Corps, 11th Battalion, Suffolk regiment

Regimental Number 16703

Private

Machine Gun Corps, 11th Battalion, Suffolk regiment

Regimental Number 16703

Son of Ellen and Herbert Norman of Town Hall Cottages, Melbourn Street, Royston, born Guilden Morden 1896.

Prior to enlisting in November 1914, he was employed as a Chauffeur to Mr C. V. Grundy of Royston. Private Norman was sent out to France in January 1916.

The following account is from a taken from a survivor of the first day of the Battle of the Somme from the 11th Battalion who gave an eyewitness account of the action. He described:

"On July 1st the 11th Suffolks were on the right of Albert when at 7:30am we left our trench to tell Mr Germany that it was time to get moving. A great many of our Brigade not being bulletproof fell before they reached the German line, for the Germans were mowing the grass with machine gun fire. I managed to cross the enemy's front line, when I halted and looked around for my comrades. The nearest of them were about 50 yards away, so I thought I would wait for the reserves to come up. As I was standing there I felt something hit my left-hand top pocket, which reminded me I'd better move. I did so and a few minutes later a bullet passed through my left wrist."

Quote from Corporal R.Harley (11th Battalion Suffolks) of March

Letter from Warrington Hospital published in the Cambridgeshire Times.

(Thanks to Cliff Brown for supplying this quote).

Private Herbert Edwin Norman was killed in action during the assault and is buried at the Ovillers Military Cemetery and remembered on the Royston War Memorial.

William Ellis Reed

Private

1st Battalion, Bedfordshire Regiment

Regimental Number 8571

Private

1st Battalion, Bedfordshire Regiment

Regimental Number 8571

Eldest son of William and Alice Reed of The Mount, Royston. He was an attendant at Arlesey Asylum at the outbreak of the war. He served in Africa, Bermuda and Gibraltar. He fought at La Bassée and Ypres.

"We went into the trenches and spent 48 hours there. On Christmas Eve the Germans were singing and shouting nearly all night and asking us to go over and have a drink of lager beer, cocoa or anything we liked to ask for, but of course no one went. On Christmas morning they gave us a nice reveille of 18 shells but no one got hurt. Then they did not trouble us anymore until midday when they started to shout and ask us to go over.

"We gained permission from our officer to challenge them to come to half way and we got out of our trenches. When they saw us they came to meet us and one or two shook hands. They sang us a carol and we sang one. After that we all joined up and sang “Tipperary” and gave three cheers for King and Country. We exchanged fags and tobacco and, when we returned to our trenches, it was agreed not to fire until 12.00 the next day.

"So you see although they were our deadly enemies we can behave as friends on Christmas Day. They told us that they were not there to fight and that they were the Landstrum (what we call our last to call upon) and no doubt they were, for only one young man was among them and he was knocked kneed and weary. The rest were all old men with long beards and appeared to be 50 years of age."

Private William Reed died 30th March 1915 and is remembered on the Menin Gate Memorial.

Copyright The What Royston Did Project Team

Except where stated, the content of this website is the copyright of the What Royston Did team and cannot be reproduced in any form without written consent.